“I fart in your general direction” - Frenchman, Monty Python and the Holy Grail

When oil wells are drilled, they produce three things in varying ratios depending on where you are in the world: oil, natural gas, and brine water (waste product). Of these three, oil is by far the most valuable and is the primary economic incentive behind the entire industry. Natural gas is a slightly different story for two key reasons. Primarily, it has a much lower volumetric energy density (Energy/Volume), ~1000x less. So for equivalent volumes (at atmosphere) the gas contains a lot less energy. Secondarily, gas is considerably harder to transport. The typical solutions are to build a gas pipeline, which is too expensive for smaller wells that produce less gas, or compress it and truck it. Which while cheaper than a pipeline, if the well is in a remote area, often isn’t economic either.

The ultimate resolution to these challenges is often that it costs more money to transport the natural gas than you can make selling it. So, the simplest and most cost-effective solution is often to just burn it. This is what is known as gas flaring. According to the most recent data, 918 million cubic feet (cf/d) of natural gas is vented or flared in the US every day. For context, the average American home uses just under 18 cf/d. In other words, the daily gas usage of 5.1 million homes is being burned or directly vented to the atmosphere every day. This represents a massive waste of energy and potentially a very large opportunity. Let's talk about crypto.

Crypto is complex, and I lack both the expertise and the word count to explain it thoroughly. While I will cover some technical details, there are many excellent resources worth exploring if you want more information. In this context, crypto mining, or more specifically Bitcoin mining, is a process that converts energy and computing power into money. Energy x GPUs = Money (not a real formula). If we simplify the process to these two key inputs, there are two main costs: the physical mining hardware and energy. Mining hardware can be difficult to purchase at a significant discount, so profitable operations are generally seeking the same thing—cheap energy. Mining is all about achieving the lowest cost per kilowatt-hour ($/kWh), and the excess natural gas we discussed earlier could potentially represent a very inexpensive source of energy. So how would this work? Well, the simplified process could resemble the diagram below:

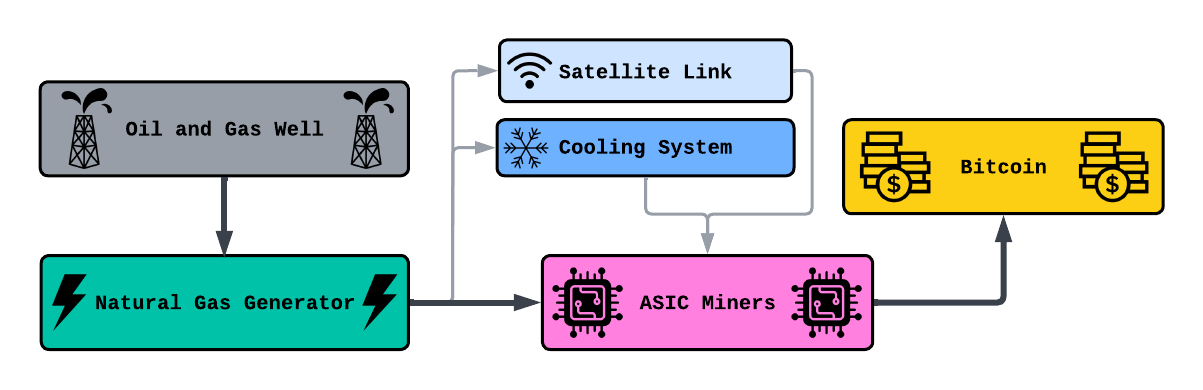

Simplified Process Flow Diagram

Interfacing directly with an oil and gas well, you divert the gas that would typically be headed for the flare and instead route it into a generator designed specifically for natural gas. Gas goes in, power comes out. Your primary power draw will be your ASIC miners (specialized hardware adapted to mine Bitcoin), and a small portion of this power goes to a cooling system and a satellite connection (e.g. Starlink), as most production sites are in remote areas with limited access to network infrastructure. The output of this process will be Bitcoin.

With the basic framework established lets get more into the nitty gritty of the economics. In this system there are four primary cost drivers; miners, a generator, a satellite link, and a cooling system. Bitcoin mining, like many industries, benefits from economies of scale so you can amortize your fixed costs over a larger number of units. This means we need a high miner count and a large generator (or generators) to provide them with power. Large generators are also cheaper per kW produced which further helps our economics. A typical 500kW natural gas generator will cost you about $500/kW while a 5000kW generator will reduce costs by 20% to $400/kW. So as a general rule we want the biggest generator and the highest number of miners. The bigger the better.

The other two cost drivers are more nuanced. Before we get into why we can use a low bandwidth satellite link as opposed to a typical fiber optic connection typically required for use in data centers, we need to understand a little more about the basics of Bitcoin. Bitcoin “mining” means to reverse engineer a cryptographic hash function such as SHA256. This hash function takes an input (which can basically be whatever you want), and converts it into a seemingly random set of 256 bits. The key is that it is effectively impossible to determine what the original input was from the output and the only real way to find it is to guess and check. However, once you have the input it is very easy to verify the output as any given input will always generate the same output. The compute power of miners is measured by hashrate which can be thought of as guesses per second. For context, most miners are measured in terrahash (TH/s) which is trillion guesses per second.

Roughly every ten minutes a new output (a string of 256 bits) is generated and broadcast to all the miners on the network who then race “guessing and checking” to find the original input. An important note here is that the miners don’t actually need to correctly solve all 256 bits (this would be incredibly hard even given the total computational power of the network). Each output starts with a certain number of zeros and a correct input is one that generates an output with an equal number of zeros. Whoever figures it out first will broadcast that input back out to the rest of the miners who can verify it is correct. When this happens, a certain number of bitcoin is generated and given to the miner who solved the hash, these are called block rewards.

So how does this relate to a low bandwidth satellite link? It all comes down to what is actually being communicated across the network. While bitcoin mining uses an incredible amount of computational power, it doesn’t actually need to communicate very much with the network. The only signals a mining operation is sending and receiving are it’s solution to the hash and the original output from the network. All in, a single miner, when configured correctly, will only consume about 30 MB/day (about a minute of instagram reels) and each additional miner will consume significantly less data. The end result is that we can use a single satellite connection to send data around instead of digging fiber optic to wherever our operation is. This means our satellite connection can also benefit from economies of scale. Since we only need a single satellite connection we can spread this cost out across all our ASIC miners.

Finally, lets talk about the cooling system. Currently, the industry appears to be favoring water cooled setups as opposed to the standard air cooled rigs. In light of this, water will be the cooling method of choice.

A water cooled system of this kind is fairly simple on the surface. We can string a bunch of these together and use a pump to carry water through the whole system. We can then hook a radiator into our system to cool down our water and voila a cooling system. We can simplify this cooling system into two primary costs; a radiator and a water pump.

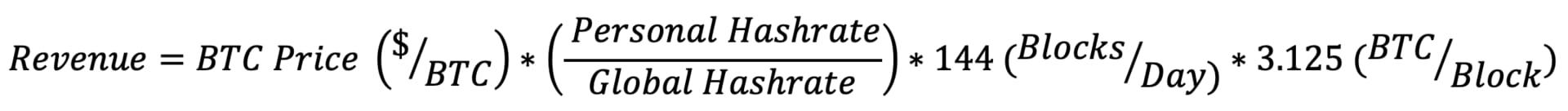

We have covered costs, now lets cover revenue. The revenue formula isn’t actually that difficult. Effectively it operates on the assumption that whatever percentage of the the global bitcoin mining network you own you will make that same percentage of the total rewards allocated every day.

BTC Price → current price of Bitcoin

Personal Hashrate → combined mining power of all personal miners (TH/s)

Global Hashrate → mining power of the entire BTC network

144 → A new block is issued roughly every ten minutes. (1 Block/10 min) x (1440 min/Day)

3.125 → This is the current reward per “block”

So would a system like this even work? Lucky for us, we have a pretty good case study to look at. Remember this picture?

Crusoe, a Colorado based company, was founded back in 2018 on the exact thesis we have been discussing, that wasted flare gas could be put to good use mining cryptocurrencies. Since then it’s growth has been explosive. Last year, in 2025, the company raised over 1B in funding putting its total valuation at over 10B. While a large portion of this valuation is due to Crusoes recent transition into AI data centers, the original thesis remains sound…plus they raised over half a billion dollars in funding prior to this transition.

Crusoe isn’t a public company and therefore isn’t required to report financial data. So while we can’t know for sure we can use our revenue formula from earlier to squint at what the numbers could be. Prior to divesting it’s bitcoin mining operation to NYDIG, Crusoe had 250 MW of power dedicated to mining bitcoin. Pulling that number into the present day we can also assume Crusoe is using the current most profitable miner, the Bitmain Antminer S23 Hyd 3U, consuming a whopping 11,000 W (22x what your fridge uses). With 250 MW Crusoe could set up 23,000 miners and with a hashrate of 1160 (TH/s) each, Crusoe could be earning a cool $400 million a year in revenue.

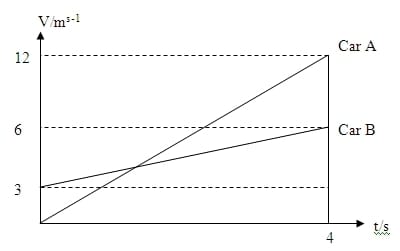

Compared to it’s grid connected counterpart Crusoe operates with some unique economic. If we compare Crusoe and a similarly sized operation connected to the grid we can highlight this difference. The traditional model involves building infrastructure, purchasing miners, and then (this is the important bit) paying a utility company over the life of the operation for power. Paying the utility represents a large percentage of annual revenue and if the price of Bitcoin drops below the cost of power the operator will be forced to shut down until the price recovers. Meanwhile, Crusoe will have higher startup costs but will have much lower OPEX since it won’t have to pay a utility for it’s power. This is key for two reasons. Primarily they keep all those dollars traditionally given to a power utility which significantly decreases their OPEX. It also means they never have to shut down, they are getting effectively free power from the stranded gas so once their operation is up and running the price of power will never exceed their profits. They get to run 24/7/365 paying no mind to the price of Bitcoin. Simply, they will take longer to pay off but will make more profit every year than the traditional model. Its the classic Car B leaves before Car A but Car A is traveling faster. Does Car A catch Car B before equipment must be replaced? Crusoe has bet a lot of money on the answer being yes.

This technology is not without its concerns. A lot of which, unsurprisingly, are associated with bitcoin. As anyone who has ever owned bitcoin knows, it is not a stable asset. The price swings wildly which can make revenue forecasting and investing in new infrastructure difficult among other things. Additionally, the rewards per block halve every 4(ish) years meaning that to remain at the current profitability the price of bitcoin combined with the efficiency of the miners must also double at the same rate.

Concern two. The mining of bitcoin itself doesn’t produce a net benefit to society. A major criticism of “proof of work” mining is that it consumes large amounts of energy and uses that energy extremely inefficiently. With ever growing concerns about energy supply in the United States, it’s easy to see how this technology may be unpopular. Of course, this energy was going to be wasted anyways so a case can be made that it’s better than nothing. Another plus for Crusoe is that running gas through a generator is actually better for the environment even if the mining itself is neutral.

…through a process called stoichiometric combustion, Crusoe’s Digital Flare Mitigation® technology achieves a combustion efficiency of 99.9% (versus an average of 91.1% for flares), thus reduces methane emissions approximately 99% and carbon dioxide equivalent emissions by up to 68.6%. By deploying DFM systems and eliminating long-term flares, we can clean up the least efficient parts of oil and gas production operations.

Another concern associated with Bitcoin mining is that if you are going to use cheap power to run a lot of computer servers your money may actually be better spent doing distributed computing or just building your own data center. Crusoe made the pivot to the AI sector and divested their Bitcoin operations last year in 2025. While logically it would make sense to skip the mining altogether and jump straight into AI computing, data centers are much more capital intensive and logistically more difficult since the uptime must be near 100%. Additionally, they require high bandwidth network connections which significantly increase costs. While there are larger margins to be made, mining represents a lower stakes way to use the energy.

Lastly, a key assumption is that there will be stranded natural gas that can be bought for cheap. If the sale price of natural gas skyrockets, all of a sudden the transportation economics work and your supply of cheap gas evaporates.

While not without its concerns, this technology presents a compelling economic and environmental case for a sector plagued by waste. By transforming a logistical headache into a decentralized power plant, operators can sidestep the massive costs of gas pipelines and the high OPEX of traditional grid-connected mining. While the pivot to AI data centers offers higher margins for industry giants like Crusoe, crypto mining remains a far more accessible entry point for smaller-scale operators due to its lower capital intensity and minimal bandwidth requirements.

Ultimately, utilizing stranded gas doesn’t just capture lost revenue; it also achieves lower methane and carbon dioxide emissions compared to traditional flaring. Even if the Bitcoin market remains a wild ride, the ability to run 24/7/365 on effectively free fuel creates a unique resilience that traditional models simply can’t match. Moving forward, this "digital flare mitigation" could be the exact anti-flatulence medication the US oilfield needs to turn its most visible waste into a sustainable profit center.